By Roderic F. Wye

As a medium-sized power, but one with particular global responsibilities and ambitions deriving from its position on the UN Security Council, the UK finds itself in a special situation in terms of a balancing to bandwagoning continuumFootnote1—in its response to China—in the light of the intense strategic competition between China and the US that has been emerging. The UK has until recently operated, as Australia, largely within the central hedging zone, seeking its own relationship with China, but remaining fundamentally committed to the alliance with the US. But that positioning underestimates the profound shifts that have taken place in Britain’s overall view and relationship with China. Less than a decade ago the UK was rejoicing in the so-called golden era of its bond with China, a description that seemed to be aligning the UK in some respects more closely with Chinese objectives (and certainly using Chinese-style language to describe the connection). The country is now considerably more China-sceptical.

This transition was initially gradual and marked by uncomfortable policy lurches, which appeared to derive from a lack of a clear and consistent strategic appreciation of the China challenge, and suggested a degree of incoherence in policymaking. Britain had been gradually becoming more vocal in its criticism of China and had been prepared to make political security gestures that were well understood to be irritating to China. But it remained keen to preserve and develop its economic relationship with China, though even that was increasingly a matter of contention at the political level. At the same time, the UK never wavered in taking the relationship with the US as the most fundamental and consistent element in its foreign and security policy. This did not mean blindly following every twist and turn of US policy towards China. The UK showed no interest in the confrontational trade policies introduced by President Trump and followed by his successor. Its view of the security challenge from China was of a somewhat different order from that of the US—goings on East Asia remained comparatively remote for the UK and other European governments.

Overall View of China

All of this has changed in the last couple of years. Firstly, the shock of COVID-19 and of China’s reaction to it has borne a significant impact on the global economy, trade and supply chains, which has reduced China’s attraction as a trading partner. Secondly, the Chinese crackdown in Hong Kong and Xinjiang led to a more critical view of China in most of the UK establishment. Even more fundamentally, the Russian invasion of Ukraine and ensuing reactions to it by the US, the EU and NATO (and of course the highly equivocal position taken by China) has tilted the UK decisively towards the “hard balancing” sector of the “Balancing Zone” (see Fig. 1.1 in Chapter 1 of this volume). This process has already been set in motion before the invasion—certainly in areas of technological and military security policy but less clearly in others. The announcement of the AUKUS partnership likewise represents a significant indication that the UK is moving in the direction of presenting a challenge to China’s increasing threat to East Asian security. It is worth noting that China was not directly named in the announcement of the new partnership, which was described as meant to protect the people and support a peaceful and rule-based international order, while bolstering the commitment to strengthen alliances with like-minded allies and deepen ties in the Indo-Pacific.Footnote2 The message, however, was very clear.

For many years, the UK had operated quite comfortably within the “soft balancing” subzone. “This geo-political change – the rise of China, the most important geo-political change in my children’s lifetime. It is the most important geo-political change in the 21st Century” (BBC Radio 4 2020). This thought, expressed here by the former UK Prime Minister Tony Blair, was commonplace in discussion of relations with China and underlined the on-going importance of properly and effectively managing relationships with China. The UK’s dealings with China are not simple nor straightforward. It is far more than a simple question of balancing the competing drives of commercial engagement while speaking up on human rights, as the relationship was frequently boiled down to, in public discourse. It is a wide-ranging relationship, covering many areas of activity. This obviously encompasses politics and economics, but also includes education, science and technology, culture and so on. Until recently, China did not figure high on the UK’s list of priorities, nor was the bilateral relationship between China and the UK given much academic or think tank consideration. This changed in recent years and there has been a string of well thought and persuasively argued considerations regarding the nature of the relationship and where it might be headed (Parton 2020a; Gaston and Mitter 2020; Kerry Brown 2019; Policy Exchange 2020). There are also a number of publications taking a closer look at the more interventionist policies pursued by the Chinese government and how these are beginning to impact on parts of UK society (Parton 2019; Hamilton and Ohlberg 2020; Henderson 2021).

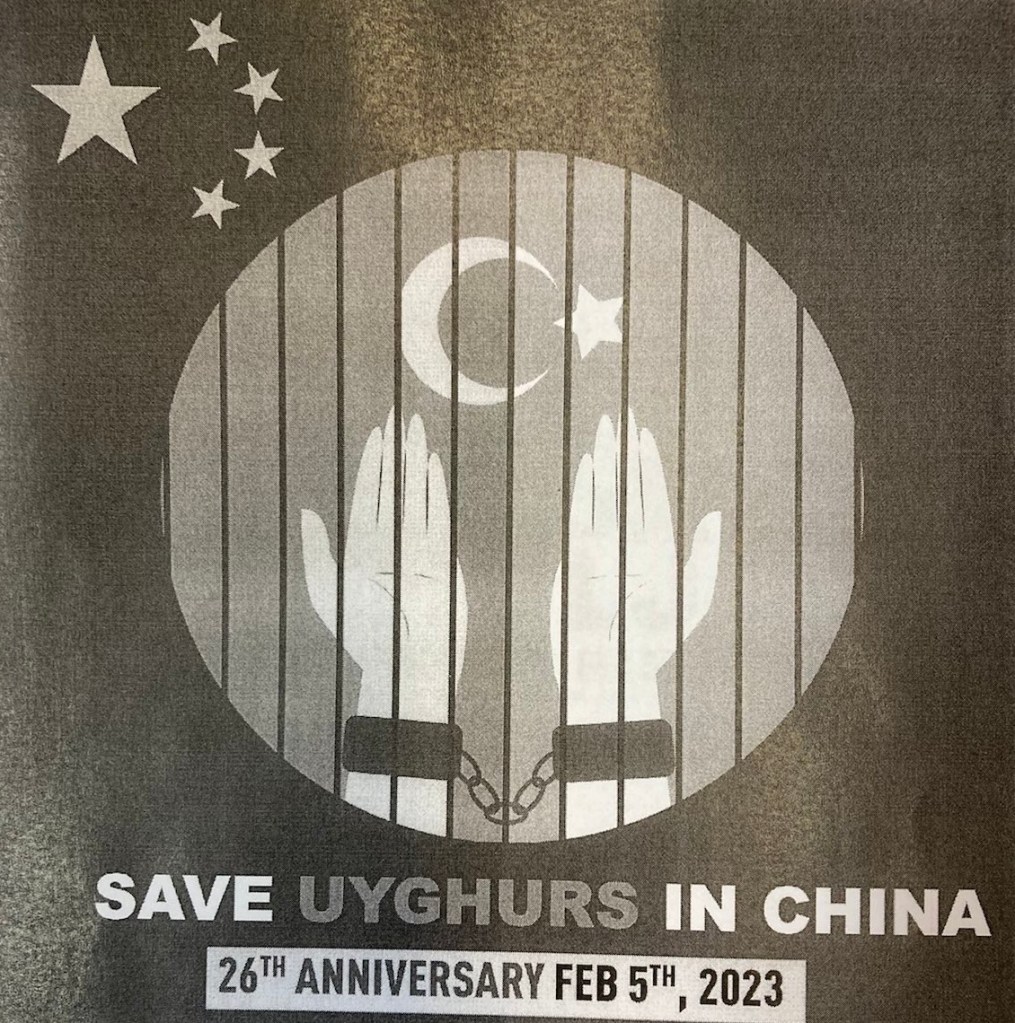

As a case in point, the debate and public hesitancy over the decision as whether to allow Huawei to provide significant amounts of the future 5G network in the UK, followed by a similarly confused trail of decision-making, leading to the exclusion of Chinese firms from the project to build a nuclear reactor at Sizewell B, have served to underline the complexity and challenges of the relationship with China. The revelations of the establishment of a vast network of camps to control and subdue the Uighur population of Xinjiang, and the ruthless way in which China has imposed its will on Hong Kong, have highlighted the authoritarian nature of the Chinese government. The behaviour of the Chinese government and its role in the outbreak of and response to the COVID-19 pandemic has likewise deeply influenced public and official views of China and of how the UK should relate to it, prompting a profound re-evaluation, even before the decisive shift in UK policy, which seemed to follow Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The necessity for a re-evaluation—or reset in the words of Mitter and Gaston (2020)—of the relationship has come at a time of profound and rapid changes in the international and geo-political situation. A crucial structural factor arises out of the marked shift in comparative power between Britain and China, since China was able to overtake the UK in economic size almost 20 years ago; this, in turn, led to a situation which makes it easier for China to take the lead and the initiative in many areas (Summers 2015). The immediate effect of the invasion of Ukraine has been to shift UK policy decisively, at least in the security sphere, towards the “hard balancing” subzone, set in the “balancing zone” rather than in the “hedging zone”. How long this effect will continue and how much it will influence other aspects of the relationship is as yet unclear, but it is certain that a milestone has been passed.

Key Historical Features of the UK-China and UK–US Relationship

Among the middle-sized powers, the UK has a number of particular features which complicate the management of its relationships with both China and the US. These include: its historical bond with the US (the so-called special relationship); Britain’s decision to leave the European Union (Brexit); Britain’s own position as a middle power deriving from its historic legacy; and Britain’s historical relationship with China.

Britain has regularly played up its special relationship with the US—deriving ultimately from the Second World War and visions of the UK’s role, which are still deeply embedded in the UK’s political consciousness. But the relationship has historically tended to mean more to the UK than to the US, which sees the value and indeed the “distinctiveness” as much more limited. There have been periods when the UK liked to imagine itself as some sort of “bridge” both in the transatlantic relationship (particularly with the European Union), and sometimes in the relationship with China. In the latter case, UK policymakers have at times believed that they could nudge the US in a more sensible direction whenever the US seemed to have slipped off course. Brexit, however, has greatly reduced the UK’s foreign policy influence within Europe and the opportunities for the country to act as some form of transatlantic bridge.

The UK, however, has been very much ahead of other European countries in its provision of rhetorical and actual support to Ukraine since the invasion, perhaps reverting to its more traditional position as a faithful supporter of the US standpoint. How much this may influence the EU in its actions and posture towards the UK is still unclear but what is clear, is that the Ukraine crisis has caused a fundamental rethinking of Europe’s security architecture, which has a profound impact also on the UK-EU relationship.

Britain’s decision to leave the European Union will have long-term consequences for the conduct of its international relations as well as for its commercial trading relations. In the context of its interactions with both China and the US, it has left the UK more exposed and deprived it of whatever leverage it had had, from being at the heart of the counsels of the European Union. In trading terms, it put the UK firmly in the position of a “demandeur” with both China and the US in that it will be seeking new (and more favourable) trading arrangements with both of them. Given the transactional tendencies of both China and the US in this area, it is likely that significant prices will be demanded by both for any new arrangement, which the UK, without the backing of the EU, will find harder to resist.

Britain occupies a particular position as a middle-sized power. It is more involved than most of its peers in international governance structures. In particular, it is one of the Five Permanent Members of the UN Security Council. This gives the UK a wider direct interest in international affairs and governance. Britain has tended to place much emphasis on the rules-based international order and to have been an eager participant in multilateral organisations. This is of course a position not that different from many other middle ranking powers, and until recently was one shared partly by China, which saw the multilateral system as a potential constraint on the US exercising unfettered influence in the world. China has stepped up its own involvement in the UN and other global governance systems, and suspicions of Chinese motivations (especially their desire to fundamentally reform the global governance system into a more China friendly model) have arisen. This more outward-looking posture on the part of China emerged at a time when, under President Trump, the US was withdrawing from significant parts of the system, viewing the whole with suspicion. This process has partially been reversed by President Biden, but in terms of international governance Britain is positioned in a potentially more confrontational situation vis a vis China and its ambitions for the future international system than many medium powers. Suspicion of the impact and even more of the intentions of China with regard to the rules-based international system, is growing in the UK. This was the subject of a major investigation by the Foreign Affairs Committee of the House of Commons, which was highly critical of China’s activities and the ineffectiveness of the UK reaction to them (HC 2019).

The historical relationship between Britain and China remains a strong influence on the future development of the relationship and has had a more profound impact on Chinese views of and policy towards the UK, than vice versa. UK politicians have by and large been either unaware of or dismissive of history, while historical interpretations of the last 150 years have been fundamental in constructing the PRC narrative of its own foundation. As a former imperialist power, Britain has impinged on many of what are now called China’s core interests in more direct ways than most other middle powers. In recent years, with the exception of Tibet, the position of the UK government on these issues has become generally tougher, primarily in reaction to perceptions of actions by the Chinese government, which substantially altered the status quo on the ground in many cases.

Regarding Taiwan, Britain, alone among countries that formally recognised the PRC, for a long time maintained a formal presence in Taiwan in the form of a Consulate accredited to the provincial government. This remained open until the exchange of Ambassadors with the PRC in 1972 (Britain thus pulled off a sort of two China policy with a Charge D’Affaires Office as its diplomatic mission in China and the Consulate in Taiwan). It may all seem a long time ago but remains an example of UK double standards from a Chinese perspective. Britain was still comparatively cautious in developing its formal relations with Taiwan and in the degree of support it gives Taiwan’s aspirations for a greater presence in international fora. But post-Ukraine, this position changed significantly, in particular the UK has been prepared to acknowledge publicly security discussions with the US on Taiwan (Sevastopolou and Hille 2022), which was immediately denounced by China as an attempt to internationalise the “Taiwan issue”. The Foreign Secretary in more than one occasion has explicitly referred to Taiwan being a security concern for the UK. “We need to pre-empt threats in the Indo-Pacific, working with allies like Japan and Australia to ensure that the Pacific is protected. And we must ensure that democracies like Taiwan are able to defend themselves” (Truss 2022).

The historical relationship between the UK and Tibet can similarly impinge on dealings with China. Under Tony Blair, the UK government attempted to remove the irritant of Britain’s rather odd (and historically based) formal position on the status of Tibet, which was based on the unusual concept of suzerainty, deriving from the relationship between the Qing (Manchu) Empire and Tibet. Britain made a unilateral and formal statement in October 2008, consistent with that of other Western countries, that Tibet was a part of China. The hope was that this statement would enable Britain to continue to make its views known on the situation in Tibet, but without the sting that it somehow gave political cover to Tibetan political aspirations.Footnote3 As is often the case with unilateral concessions to China, said statement won no favours and was probably a factor in the strength of the Chinese reaction to the decision of Conservative Prime Minister to meet the Dalai Lama (albeit in a religious capacity) in 2014. Currently, there are very few reactions from the British government about Chinese actions in Tibet.

For a long time, Britain did not harbour any direct interest in the South China Seas; indirectly, though, Britain’s historic position as a major trading power and upholder of the freedom of navigation clashed against Chinese claims and aspirations in the region and the UK, like the US, has conducted Freedom of Navigation Operations in the Indo-Pacific. In September 2020, the US Ambassador to Britain tweeted with regard to the proposed deployment of the UK carrier group: “We welcome the UK joining us and other allies in calling out China’s unlawful maritime claims in the South China Sea” (as quoted in McGleenon 2020). Naturally, the Chinese interpreted this as evidence of the UK ganging up on China. A Foreign Office Minister told Parliament in September 2020 that the UK has, as a matter of principle, sent Royal Navy ships to transit the region on 5 occasions since April 2018. These were intended to exercise freedom of navigation rights as well as to further defence engagement with regional partners. The message was meant to convey the idea of the UK being prepared to engage more directly in regional defence mechanisms, with allies and partners (in particular with the US) (UK Parliament 2020). In an unusual joint action with Germany and France, the UK has twice, in 2019 and 2020, made representations on the South China Sea. In August 2019, they issued a joint statement outlining their concerns about the situation in the South China Sea (Foreign and Commonwealth Office 2019). On 16 September 2020, the three countries submitted a joint Note Verbale to the United Nations questioning China’s historic claims in the region (Chaudhury 2020).

Last of the major historical issues and the most obvious is Hong Kong. The recovery of sovereignty over Hong Kong had been a historic mission of the Chinese Communist Party, for a long time. Negotiations over the future of the city, which began in 1982 and led to the signature of the Joint Declaration (the framework, mandating that the system in Hong Kong would remain unchanged for 50 years after the handover in 1997), dominated Britain’s relations with China at least until 1997. Since China has increasingly tightened its control over Hong Kong through the passing of the National Security Law in 2020 and the subsequent removal of pro-democracy legislators, Britain has taken a more vocal stance and indeed taken actions such as the enabling of British Nationals Overseas (a special form of British Nationality accorded to pre-handover residents of Hong Kong) to have a route to full British citizenship. China now claims that the UK has no legitimate standing to speak on Hong Kong issues, and that the UK’s obligations and rights under the Joint Declaration ceased on 1 July 1997. The UK, on the other hand, believes that it has both the right and obligation to see that China lives up to the commitments, as stated in said document. Hong Kong related issues have flared up regularly since 1997, mainly centring on the pace of political reform in Hong Kong, and will continue to do so as China seeks to extinguish any form of opposition or dissent from its rule in Hong Kong. Britain has moved from a position of considering that the “One Country, Two Systems” arrangements were continuing to work satisfactorily in general, to one where clear breaches of the Joint Declaration are regularly called out. The UK Government’s Six-Monthly Report to Parliament on Hong Kong now states unequivocally: “this period has been defined by a pattern of behaviour by Beijing intended to crush dissent and suppress the expression of alternative political views in Hong Kong. China has violated its legal obligations by undermining Hong Kong’s high degree of autonomy, rights and freedoms, which are guaranteed under the Joint Declaration” (Six-Monthly Report 2021).

Relationship with China

Against this historical background, the UK generally sought to maximise the commercial benefits of its relationship with China and tried to compartmentalise the commercial relationship from the political one so that difficult and sensitive political issues did not, as far as was possible, damage the commercial relationship. This did not mean that political issues were neglected and indeed there were occasions in which, perceived transgressions by the UK in the areas designated as core interests by China, did impact the relationship. The most serious in recent years was the freezing of contacts following Prime Minister Cameron’s meeting with the Dalai Lama in 2013; there were other regular incidents over the years, when the UK infringed on China’s definition of what was permissible.Footnote4 The freeze on David Cameron was only relaxed after the UK publicly declared that such high-level meetings would not happen again (Watt 2013). While such meetings did not, indeed, happen again Britain has become markedly less concerned about insulating political and security matters. In the context of post-Ukraine sanctions on Russia, the Foreign Secretary has explicitly warned that “countries must play by the rules. And that includes China” (Truss 2022).

Britain’s approach to China has remained relatively consistent and predictable over a long period, at least since the raising of relations to ambassadorial level in 1972. Until a few years ago, China was not perceived as a serious domestic political issue in the UK. Even during the lengthy period of negotiations over the handover of Hong Kong, there was general cross-party agreement both on the overall negotiating approach and on the need to continue dialoguing with China. Recently, the UK bought into the general consensus that the most effective way to manage the relationship with China was through engagement and by bringing China into the global rules-based system. In fact, the country’s rapid economic development was considered less as a challenge and more as an opportunity for the British business sector seeking a market to sell its products and as a source of needed investment.

However, the share of British investment in China was considerably greater than the share of Chinese investment in the UK, so that the balance of trade was substantially in China’s favour. Moreover, Chinese investment in the UK has generally not been credited with creating significant numbers of new jobs and overall to be distant from the initial official description. Furthermore, Chinese investment in areas of critical national infrastructures has become a matter of direct political and security concerns. This was noted in the Integrated Review, and the government’s reaction to growing concerns included the introduction of a National Security and Investment Act to allow the government greater powers to scrutinise foreign investments in sensitive area. In the case of China, the course of the debate over Huawei’s involvement in the telecommunications infrastructure and the Chinese investment in Hinkley Point C nuclear reactor followed a similar course, moving from rather complacent acceptance of the investment as crucial to the development of the project, through growing scepticism and reassessment, to eventual seeking ways to remove the Chinese party from the projects. Despite this growing concern over the risks of Chinese investment Prime Minister Boris Johnson declared in October 2021 that Britain would not “pitchfork away” from Chinese investment, and that China would continue to play a “gigantic part” in UK economic life for years to come (Cordon and Gibson 2021).

The view from the top, engagingly presented by Nick Robinson in his radio programme Living with the Dragon (BBC Radio 4 2020), is that for the last twenty years or so there was really no alternative for the UK but to engage fully with China. China was seen as “one of two indispensable powers, if you want to get something done, you need China as part of the equation” in the words of David Miliband, former UK Foreign Secretary. This was very much the thinking behind the only public strategy on China that the UK has had (The UK and China: A Framework for Engagement 2009). In this document, published in 2009, the UK set out its policy towards China in some detail—but the clue is in the title (engagement). The UK had bought fully in to the prevailing consensus that the way to deal with and manage China’s rise was to engage with it. The predominant view across the Atlantic was that engagement was “influencing China’s evolving domestic polices, helping China manage the risks of its rapid development, and over time, narrowing differences between China and the West. Greater respect for human rights is crucial to this”. It is clear from this that the narrowing of the differences was conceived as China becoming more like us than vice versa. David Miliband was bit more nuanced and less ambitious when quoted in Living with the Dragon: “There was a view that by embracing China in the global economic system the notion of a rules-based order would grow. I don’t think we should ever confuse that with a belief that somehow democracy was going to sprout in China. There is a very big difference between accountability of government and following the rules and democratic government” (BBC Radio 4 2020). But part of the aims of the engagement policy was, even though not explicitly stated, to facilitate the process of converting China into a more “democratic” and rules-based country.

The engagement process culminated in the “Golden Era”—widely seen as the total predominance of commercial interests over other more sensitive political aspects of the relationship. But there was a wider vision than simple commercial benefit, on the UK side. This concentrated mainly on the need to engage China in the major global issues of the moment. George Osborne claimed that the real meaning of the Golden Era was that they were: “upgrading our relationship with one of the world’s emerging superpowers from being a strictly commercial one and rather transactional to a much deeper relationship where we tackled the big issues facing the world together; like the global economy, climate change…we would not always see eye to eye with the Chinese but we would at least be engaging with real players in the world” (BBC Radio 4 2020). It would appear that aspirations for changing China for the better had by then largely fallen off the agenda. It was after all post-financial meltdown, and the appetite for changing China—especially when based on some implicit assumption purporting the superiority of the Western model—had rather lost momentum. China was in no mood to be lectured any longer by Western countries. But there was no holding back on engagement: “the more we extend the hand of friendship to China, the more we are able to increase our influence in the world and the more we are able to have the kind of candid conversations about the kind of things we don’t want them doing” (BBC Radio 4 2020). Britain sought explicitly to be China’s best friend in the West (Phillips 2015). President Xi Jinping, about to set off on a State visit to the UK, praised the UK’s “visionary and strategic choice” in declaring that it intended to become the Western country that was most open to China. Today, it is hard to believe that such a statement was made by the UK government. A study by the European Think Tank Network on China published in 2020 on the EU’s relations with China found that: “…every European country claims to be China’s ‘best friend’, or ‘best partner’, or at least its ‘entry door’ in Europe. Hence, it seems that China has managed to create ‘28 different gateways to the EU’” (Huotari et al. 2015).

The Cameron/Osborne government aspired to make China Britain’s second-largest trading partner within ten years. Such aspirations, however unrealistic, continue to be partially entertained. One of the post-Brexit targets of the UK government will undoubtedly be to agree to new forms of trading arrangements with China. However, a recent study suggested that political constraints imposed on the UK by its existing partners, the US and the EU, would seriously limit the room for manoeuvre that the UK might have in negotiating a future economic partnership with China (Crookes and Farnell 2019). The Chinese will be pressing hard for concessions from the UK that are likely to help them in their future negotiations with the EU, whose own negotiations with China over a Comprehensive Partnership Agreement and an Investment Treaty (CAI) were proceeding with customary glacial slowness, only to be stymied in the European Parliament and effectively shelved for the time being. Britain might have hoped, for example, that an undertaking to accord Market Economy Status (MES) to China (something the EU has long, and for good reason, refused to do) would ease the way to some useful concessions on matters of interest to the UK (for example in financial services). But the reality is that the Chinese would likely see such a move for the empty gesture it would be. They would pocket the concession (and hope to use it to put pressure on the EU) but this would have little value to them. The Chinese have themselves called time on their attempt to secure MES through the WTO.

Relationship with the US

Under the Trump Administration—and the manifest lack of substantial reform in China—an isolationist turn took place in the US, which manifested into an inward-looking series of policies, distancing from engagement and increasing vocal rhetoric of China as a competitor. The US State Department, in a conscious echo of the Kennan telegram, which outlined US policy for the Cold War, published a lengthy assessment of China and the challenge it poses, which sums up the then thinking of the US Administration, in November 2020. It is an unremittingly sceptical if not hostile assessment: “The CCP aims not merely at pre-eminence within the established world order — an order that is grounded in free and sovereign nation-states, flows from the universal principles on which America was founded, and advances U.S. national interests —but to fundamentally revise world order, placing the People’s Republic of China (PRC) at the center and serving Beijing’s authoritarian goals and hegemonic ambitions” (The Elements of the China Challenge 2020). To the UK, however, the concept of competitor (in a political rather than a free market commercial sense) was until recently pretty alien and the UK seemed to be moving further towards the US perspective on China. The US, even under the Obama Administration, was very uneasy about the UK decision to be amongst the early participants in the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). In the words of one US official quoted in the Financial Times: “We are wary about a trend toward constant accommodation of China, which is not the best way to engage a rising power” (Watt et al. 2015). Interestingly enough, Ambassador Liu Xiaoming was later to single the AIIB decision out as one of two instances when the UK got relations with China spectacularly right (the other was recognition of the PRC in 1950, again an instance where the UK departed significantly from the US position) (Chinese Embassy Press Release 2020). He also made it clear, though not explicitly, that in both those decisions the UK had defied pressure from the US to side with China—a path he urged upon the UK: “I often say ‘Great Britain’ cannot be ‘Great’ without independent foreign policies. The UK has withstood the pressure from others and made the right strategic choices at many critical historical junctures” (Ibidem).

While the UK has generally been in tune with the US over its approach to China, it has sought to manage that relationship separately from its relationship with the US. In the context of a general consensus on the overall approach to China, the UK has not shied away from taking actions that the US did not agree with: one could start way back in the 1970s with the raising of Ambassadorial relations (all this before the famous Nixon visit that precipitated more positive relations between China and the US). Later on it sold advanced military equipment or sought to—for example, the consideration given to selling the Harrier Jump Jet—to China (Bhardwaj 2016). UK sourced jet engines played a significant part in the past in upgrading China’s military air force capability. None of these actions was well received by the US. Equally, there have been times when US pressure prevented the UK from taking actions it might otherwise have taken: the most recent example is perhaps the UK’s decision, after much toing and froing, to remove Huawei equipment from its future 5G network. The long debate within the European Union about lifting the 1989 EU Arms Embargo, an idea of which Britain was in favour, was eventually shelved because of US objections (Congressional Research Service 2006). Certain Chinese sources were still complaining about this, and urging the lifting of the embargo, many years later (Global Times 2017). Notably, the UK recently (July 2020) extended the Embargo to Hong Kong (which had previously deliberately been exempted) as part of its response to the introduction of the National Security Law (Foreign and Commonwealth Office 2020a).

Overall, the UK assessment of the security threat or challenge coming from China has been for the most part much closer to the European perception than to that of the US. It is only quite recently that the UK has begun to take the security threat from China seriously, especially in regards to cyber and other forms of interference in the UK system. Until recently, China was not perceived as posing an actual security threat to Europe. For Europeans, the principal threat is still Russia and Europeans (and of course the British) have been more willing to accommodate Chinese military ambitions than the US. They have been slower to acknowledge the overall challenge that China is posing to the established international order. This, however, has started to change a few years back. In 2019, for the first time, an EU paper on the relationship with China described the PRC as a systemic rival (European Council on Foreign Relations 2020). The UK is moving towards a more confrontational posture, with regard to China on security issues—as emobodied by the AUKUS agreement, and the despatch of a naval task force to East Asia—and more recently through the Foreign Secretary’s statements on Taiwan. As noted above, this process has been hugely accelerated, following the Ukraine crisis.

The US’ perspective regarding the security threat posed by China has always been different. The UK shares some important positions of principle—for example, over the Freedom of Navigation (FON) where UK (and French) vessels have taken part in FON exercises in the South China Sea. In this case, US and UK interpretations of the access allowed to military vessels on the high seas are one and the same, and in conflict to what China sees as its rights in the South China Sea. To this regard, the UK deployed its new carrier task force in the Asia Pacific more as a political than a military gesture. The actual UK’s capability for playing any significant role in a potential conflict in the Indo-Pacific region is limited at best. Nor is the balance of power in the Asia Pacific anything in which the Europeans or the British now feel they have any real leverage on (though both the British and the French have colonial legacies in the region). The UK still has a global reach and has been prepared to join US-led initiatives in the Middle East and elsewhere but not in East Asia. In the past, the UK conspicuously kept away from direct involvement in Vietnam. There is no equivalent to NATO involving the UK directly in the defence and security arrangements of the region. There is the Five Power Defence Arrangement (The Diplomat 2019), which provides a semi-formal UK commitment to defence in the region. This has been primarily focussed on Singapore and Malaysia and was initially not established with China in mind. But it is a potential vehicle for greater UK involvement at the political and military level in the region, which China increasingly sees as its backyard. With the UK fixated on its relationship with Europe and the trade and commercial relationship with the US, there was not much room for imaginative thinking on Asia and Asian security. The Free and Open Indo-Pacific,Footnote5 a concept introduced by the US Administration in 2017, has not, so far, gained much traction in the UK. A recent think tank report suggested that this could change (Wintour 2020) and that the UK should play a more active role in the region; financial, conceptual and political constraints remain. The authors imagined role for the UK as a country, committed to challenging China’s authoritarian model, is perhaps too radical for any UK government in the near future (Policy Exchange 2020) but the UK perhaps underestimates its normative power and the wish of countries in the region to see the UK playing a greater role than it is currently doing. Any such action would likely receive pushback from China. Nonetheless, the UK became a dialogue partner of ASEAN in August 2021, another clear gesture of deepening UK political involvement in the region (British Embassy Manila 2021).

Until recently the so-called five eyes intelligence and security relationship was not seen as having any particular impact on the conduct of international affairs. It arose from the close UK/US intelligence relationship in the Second World War, and was later expanded to close English-speaking allies, but it was very much a relationship, based on intelligence-sharing. There was never a sense of it being a formal treaty alliance. It gained more currency recently in the discussions of reactions to Huawei. The 5 Eyes partners have seldom if ever acted explicitly in concert on the international stage. This is now beginning to change, especially in the context of managing relations with China. The five governments have, on a couple of occasions, jointly issued statements of condemnation of Chinese behaviour over Hong Kong (Foreign and Commonwealth Office 2020b). This provoked a strong attack from the Chinese side on the grouping for daring to act in concert and daring to be critical of a Chinese internal matter (BBC News 2020). So far, there has been only weak pushback from New Zealand to the blast from China and a studied silence from the other partners. It is noticeable that the issuance of the statement was not done in coordination with the EU, although the EU did issue separate statements of its own. From a UK perspective, it perhaps does offer an established channel for bringing allied pressure on China. Ideas vented from Japan to expand the grouping into something more formal, with the inclusion of Japan into the relationship, have met no response (Panda 2020). There is no formal organisation for the 5 Eyes, no secretariat, and it is likely to remain simply an ad hoc, informal, channel for occasionally reinforcing and strengthening areas of pushback against the Chinese state.

Finding the Balance: Allies

Managing relationships with China and with the US are key foreign policy challenges for most middle-level powers. It is no longer possible to deal with these two powers via separate bilateral relationships; both the US—and now China—understand third countries’ bilateral relationships through the lens of their own mutual relationship. In a world of increasing complexity and globalisation, middle powers have a real broad interest in managing an effective relationship with both China and the US, in such a way that does not entangle them into the bilateral disputes or forces them to take sides. The new Biden Administration in the US sought to alleviate fears that third countries might find themselves in a position of standing either with the US or with China. Even though Biden has been considerably less isolationist than Trump, there remains a concern that he will try to coalesce sceptical international partners into a new competition with China (Jakes et al. 2020). That being said, there is a recognition from the US side that a new transatlantic approach to China would be of benefit to both Europe and the US. In managing relations with China many European small and middle powers are likely to seek US backing often and share many of the US concerns with regards to Chinese commercial and political behaviour (Smith et al. 2020). Again, the Russian invasion of Ukraine has changed perceptions markedly. The British Foreign Secretary now speaks of deepening a Network of Liberty, declaring that there is “huge strength in collective action. And let me be clear, this also applies to alliances that the UK is not part of. We support the Indo Pacific Quad” (Truss 2022). This kind of discussion is of course anathema to China, and Foreign Minister denounced “strengthening the Five Eyes..peddling the Quad…piecing together AUKUS..” as a “sinister move to disrupt regional peace and security” (Wang Yi 2022).

Navigating a Course Between China and the US

Another notable factor is the increasing polarisation of domestic politics in both the UK and the US, which has a direct effect on how foreign policy decisions are seen (and indeed made), including those regarding China. China is not such a crucial political factor in the UK as it is in the US, but while there was once a broad UK consensus on its China policy, that is no longer the case. While the current US Administration may talk in a grandiose fashion of seeking to rebuild alliances, the US still tends to act unilaterally and to expect allies to follow suit and in particular to follow more its China-sceptic policies. Where domestic politics are highly adversarial there is at least a possibility that foreign policy choices will come to be seen through a similar lens. It is unlikely, for example, that the US will in any way ease up on its pressure over Huawei and on those European countries that have not taken the decision to exclude it from their 5G networks. Similarly in the UK, while China may not be high on the everyday agenda of politics, the discourse is undoubtedly becoming more politicised, especially as very real concerns about the extent of Chinese influence on UK’s politics, begin to be exposed (Parton 2019). It is no accident that the new conservative group, which is much more China sceptic than any previous parliamentary body, calls itself the China Research Group, a deliberately provocative echo of the title of the European Research Group which was one of the driving forces behind Brexit. The group states that its purpose is to expand debate and fresh thinking about China and that it is not an anti-China organisation.Footnote6 That did not save it from being on the list of UK entities and organisations sanctioned by the Chinese in response the UK sanctions imposed over Xinjiang.Footnote7 In the wider context of a growing scepticism of the efficacy of previous engagement policies in the UK and elsewhere, the point of the Group is that a radically new approach to China is needed. Those arguing most strongly for continuation of the engagement policy often put the choices in the starkest of terms. George Osborne explained the rationale behind the Golden Era policies: “we can either co-opt China into an international order that we largely created and try and make them partners in peace and stability…or we can try and contain China, launch ourselves into a second Cold War with all the risks of ultimate destruction that that brings. I still ask the question: if you don’t want to engage with China, if you don’t want to make China a partner for peace and security in the future – what is your alternative plan?” (BBC Radio 4 2020). The choice is not necessarily that stark, and there should be an alternative to unquestioning engagement largely on China’s terms. China’s uncompromising behaviour in areas such as Hong Kong and Xinjiang has hardened the public view of China. The fact that there was virtually no adverse reaction to the decision to allow Hong Kong BN(O) passport holders a fast track to British citizenship (given the overall sensitivity of immigration in UK politics) is a clear indication public opinion is becoming far more tolerant of a tougher line on China.

Navigating a course between the demands of China and of the US is not simple or necessarily straightforward. On most major issues, the UK is likely to remain aligned with the US, rather than with China. But that has not always been the case, and certainly during the Trump Administration the UK has leaned more towards China than the US on certain issues—the issue of climate change, being the most obvious and important example. Like other European countries, the UK has preferred to stand aside from the trade wars and other areas of confrontation between China and the US, though it shares many of the US’ concerns such as violations of intellectual property, the refusal of China to allow a level playing field for many forms of commercial activity in the Chinese market, unfair subsidies of State Owned Enterprises and so on. Chinese threats against the UK have grown and are increasingly being framed in terms of “choosing one side over the other”. The Chinese Ambassador Liu Xiaoming denounced the UK’s plans to deploy its new carrier group in the Far East as a “very dangerous move” signalling aggression towards China and evidence of the UK ganging up against China (Philp 2020). But such language is no longer confined to security issues. Speaking on the Huawei question on 20 July 2020, Ambassador Liu Xiaoming said: “We want to be your friend. We want to be your partner. But if you want to make China a hostile country, you will have to bear the consequences” (Financial Times 2020). He added: “The issue of Huawei is not about how the UK sees and deals with a Chinese company. It is about how the UK sees and deals with China. Does it see China as an opportunity and a partner, or a threat and a rival? Does it see China as a friendly country, or a “hostile” or “potentially hostile” state?” (Chinese Embassy Press Release 2020). The problem for countries like the UK is that it is often difficult to tell in advance what actions might be viewed as hostile by China, as the definition of what such hostility consists of rests almost entirely with the Chinese government.

There is much more robustness to China’s recent rhetoric. In the growing row between China and Australia, a Chinese official recently said “If you make China the enemy, China will be the enemy” (Kearsley et al. 2020). This was in the context of 14 complaints the Chinese government has levelled against Australia (Ibidem). None of the actions for which China complained appeared to the Australians as deliberately intending to “make” China into an “enemy” and yet the Chinese side has construed them as such. Australia seems to have become a test case, to find out how much pressure an individual country can bear. The Conservative chairman of the UK Parliament’s Foreign Affairs Committee called for the UK government to show solidarity with Australia in resisting pressure, adding that: “We see ourselves frankly as in very much the same boat as Australia” (Kearsley and Bagshaw 2020). His analysis was not that far off the mark: many of the complaints against Australia can find echoes in the complaints levelled against Britain in Ambassador Liu Xiaoming’s Press Conference which have been quoted extensively in this paper (Chinese Embassy Press Release 2020).

Some Challenges for Future Policy

It is becoming a commonplace in discussions of UK policy on China, that the UK desperately needs a new and clear strategy regarding its relationship with the PRC. There has been no formal strategy (at least no formal publicly available one) since the one by the Labour government in 2008. Such a strategy has been proposed in many of the recent think tank pieces on China and in parliamentary reports (The Security and Defence Committee of the House of Lords 2021). So far, however, there has been no public governmental response to these calls. The Report of the Foreign Affairs Committee on China and the International Rule of Law in 2019 contained detailed recommendations for the development of a strategy towards China. The government response, published in June 2019, did not address these concerns directly (Foreign Affairs Committee 2019). It concentrated on the mechanisms which already existed for directing the strategy towards China: “the overall strategic approach towards China is agreed by the National Security Council (NSC). The NSC coordinates across government and is central to ensuring an effective and strategic policy, which promotes UK values and interests”. It went on to describe frequent meetings of the China National Strategy Implementation Group led by the Deputy National Security Adviser in his capacity as Senior Responsible Officer for China. It said that National Security Strategies were not published, but gave some broad headings on which the NSC focussed in regard to China. But these gave no clear steer on the strategic perspective through which the government viewed China. Some elucidation of the merging government view was given in the Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy published in March 2021 (Cabinet Office Policy Paper 2021). This moved the UK view of China much further towards the “balancing end” of the spectrum of responses. For the first time, China was described as a “systemic competitor”, which presented the greatest state-based threat to the UK’s economic security.

What is missing is not so much a strategy, but rather a strategic and clear-eyed assessment of China’s aims and behaviours and of Britain’s interests when dealing with China. This is a complicated matter that will need to consider carefully the changes that have taken place in Chinese foreign and domestic policy in recent years.

A new question, that has risen comparatively recently, is how to respond to the new authoritarian behaviour of the Chinese government both at home and abroad. This demands a response in the area of values. One of the prime critiques of the engagement policy is that there has been a problematic under-estimation of the extent to which China has been willing to interfere and undermine democratic values in Western countries. China is using new tools and systems at its disposal more aggressively. It increasingly sees itself both in competition with Western values, and in the business of defending itself against them.Footnote8 Foreign policy based on values has had a troubled history in the UK. The attempts by the Labour Government, which came to power in 1997, to establish an “ethical dimension” to foreign policy quickly foundered. An effective way of handling the tensions between speaking out on human rights abuses and seeking commercial benefits in China is part of this, but the time may have come for values to be incorporated more seriously into UK policy as a response to the growing tendency of the Chinese state to seek to impose its view of the world on the international community. The UK, like many others, has struggled to find a way to effectively promote its values with regard to China while maintaining profitable economic ties. More often than not these two have been seen as mutually incompatible goals, and the consequence has been that the UK’s position on issues such as human rights has been comparatively muted. This is beginning to change. For the first time, the UK introduced sanctions against individuals and organisations deemed to have been involved in systematic violations in Xinjiang. This action was taken in concert with the US, Canada and the EU, but it was the first time that the UK has used such instruments in its dealings with China (Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office 2021). In a similar vein, the Integrated Review stated that the UK would: “not hesitate to stand up for our values and our interests where they are threatened, or when China acts in breach of existing agreements” (Cabinet Office Policy Paper 2021).

Britain has a major stake in maintaining the rules-based international order. China is increasingly seen as a disruptive element. The UK Parliament’s Foreign Affairs Committee conducted a major enquiry into China and the rules-based order in 2019. It concluded that: the current framework of UK policy towards China reflects an unwillingness to face the reality of China’s strategic direction. In some fundamental areas of UK national interest, China is either an ambivalent partner or an active challenger. This does not mean that the government should seek a confrontational or competitive relationship with China, or that it should abandon cooperation. But we must recognise that there are hard limits to what cooperation can achieve; that the values and interests of the Chinese Communist Party, and therefore the Chinese state, are often very different from those of the United Kingdom; and that the divergence of values and interests fundamentally shapes China’s worldview (Foreign Affairs Committee 2019).

The UK will wish to retain its close alliance with the US. Its position as a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council (also known as P5), and its historical inclination, lead in this direction. It will be more reluctant than the EU to depart markedly from the US view of China. This puts it, by default, on the harder end on the hedging zone, edging—at times—towards a more explicit hard balancing (especially in the security sphere). But there has been a wariness about being drawn completely into the US’s policy orbit. The UK has been slow to develop a more active form of pushback in relation to China. Policymakers remain perhaps over concerned at the effects of Chinese retaliation. A report for the Council on Geostrategy by Charles Parton suggests that the Chinese bark is often more serious than its bite, and that it is still possible to take stands of principle (or self-interest) without suffering long-term adverse consequences (Parton 2021). The extremes of uncritical engagement complete acquiescence in China’s agenda (often seen as a symptom of uncritical engagement anyway) and treating China as an enemy are equally unattractive. Britain will be looking for a middle way in dealing with China and the US, summed up in the Policy Exchange paper: “Finally, in upholding its values, Britain recognizes the increasing strategic competition between two competing visions of regional order, offered by China and the US. The UK does not seek any new cold wars, but it will defend its interests at home and abroad. At the same time, the UK government cannot take a value-neutral position between Beijing and Washington, nor should it see itself as leading a new ‘non-aligned’ movement of smaller states in opposition to the two great powers of the region. Britain should defend global cooperation, openness, respect for law, and adherence to accepted norms of behaviour in concert with the US and like-minded nations in the Indo-Pacific and beyond” (Policy Exchange 2020).

Conclusions

British policy towards the management of its relationship with China is evolving and changing at a dramatic pace. While there is increasing evidence that the UK government has a somewhat clearer view of its overall strategy, there has been no public announcement of any such strategy. Strategy documents can become rapidly dated but a clear statement concerning: the UK’s interests with regard to China; how those interests should be pursued; and, how the UK views the direction of Chinese policy, would allow for a more steady direction of policy, which in the last few years has been lurching unsteadily towards a more confrontational approach to China. Partly this has been caused by the mutated stance of the US towards China. While the UK has not slavishly followed US policy, the changed US view of China, and its assessment of the efficacy of the previous policies which emphasised engagement, has directly impacted the debate in the UK. China’s growth is increasingly viewed as a challenge rather than an opportunity. The actions of the Chinese government in recent years and its increasingly assertive foreign policy have forced a rethink of the relationship. British policy has moved away from one where economic considerations prevailed, to one in which the UK government has begun to push back against Chinese actions in a number of areas, and has even begun to seek ways in which it can pursue greater involvement (especially in Asia and the Pacific). The UK has been prepared to take actions (over Hong Kong, for example, and the first-ever application of sanctions in respect to Xinjiang), which ignited China’s wrath.

However, the UK remains unwilling to follow the US blindly and remains committed to developing its own relationship with China. To this avail, it increasingly looks to work with other partners, and “like minded” allies in finding common approaches to the challenges China poses to the rules-based international system. Economic factors remain hugely important but no longer in an uncritical way. In terms of the “balancing to bandwagoning” continuum, the UK appears, perhaps more by accident than conscious decision, to have moved within the hedging zone from “limited bandwagoning” towards “soft balancing”, at least in security terms. This shift has been accelerated by the rapid changes in the global environment recently, most notably the effects of the pandemic, and now the responses to the Ukraine crisis. Both these effects are still being worked through and it is too early to judge their long-term effect on the relationship.

Notes

- 1.The concept is taken from Alan Bloomfield (2016).

- 2.UK Government Announcement: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uk-us-and-australia-launch-new-security-partnership.

- 3.In a written Ministerial statement, the Foreign Secretary David Miliband said: our ability to get our points across has sometimes been clouded by the position the UK took at the start of the twentieth century on the status of Tibet, a position based on the geo-politics of the time. Our recognition of China’s “special position” in Tibet developed from the outdated concept of suzerainty. Some have used this to cast doubt on the aims we are pursuing and to claim that we are denying Chinese sovereignty over a large part of its own territory. We have made clear to the Chinese Government, and publicly, that we do not support Tibetan independence. Like every other EU member state and the US, we regard Tibet as part of the People’s Republic of China. Our interest is in long-term stability, which can only be achieved through respect for human rights and greater autonomy for the Tibetans. The text is reproduced by Free Tibet: https://www.freetibet.org/news-media/pr/britain-rewrites-history-recognising-tibet-part-china-first-time.

- 4.The visit of the former Taiwanese President to the UK, Lee Teng-hui, in 2000 provoked strong Chinese protests. See: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DtAliOXuIvU.

- 5.Free and Open Indo-Pacific is an umbrella term that encompasses Indo-Pacific-specific strategies of countries with similar interests in the region.

- 6.See the introduction to the Group on its website: https://chinaresearchgroup.substack.com/about.

- 7.Spokesperson of the Chinese Foreign Ministry, 26 March 2021. https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/xwfw_665399/s2510_665401/2535_665405/t1864366.shtml.

- 8.This approach is discussed in a recent paper by Charles Parton (2020b).

References

- BBC News. 2020. Hong Kong: ‘Five Eyes could be blinded,’ China Warns West. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-54995227.

- BBC Radio 4. 2020. Living with the Dragon. https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m000pfgz.

- Bhardwaj Atul. 2016. When the British Tried Selling Harrier to China in the 1970s. ICS Dehli Blog, May 13. https://icsdelhiblogs.wordpress.com/2016/05/13/when-the-british-tried-selling-harrier-to-china-in-1970s/.

- Alan, Bloomfield. 2016. To Balance or to Bandwagon? Adjusting to China’s Rise During Australia’s Rudd-Gillard Era. Pacific Review 29 (2): 259–282.CrossRef Google Scholar

- British Embassy Manila. 2021. UK Becomes ASEAN Dialogue Partnerx. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uk-becomes-asean-dialogue-partner.

- Cabinet Office Policy Paper. 2021. Global Britain in a Competitive Age: The Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/global-britain-in-a-competitive-age-the-integrated-review-of-security-defence-development-and-foreign-policy.

- Chaudhury Dipanjan Roy. 2020. France-UK-Germany Submit Joint Note in UN Against China’s South China Sea Claims. Economic Times, September 20. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/defence/france-uk-germany-submits-joint-note-in-un-against-chinas-south-china-sea-claims/articleshow/78191913.cms?from=mdr.

- Chinese Embassy Press Release. 2020. Opening Remarks by H.E. Ambassador Liu Xiaoming at the Press Conference on China-UK Relationship, July 30. https://www.mfa.gov.cn/ce/ceuk//eng/ambassador/t1802709.htm.

- Clive, Hamilton, and Mareike Ohlberg. 2020. Hidden Hand: Exposing How the Chinese Communist Party is Reshaping the World. London: Oneworld Publications.Google Scholar

- Congressional Research Service. 2006. European Union’s Arms Embargo on China: Implications and Options for U.S. Policy. https://www.everycrsreport.com/reports/RL32870.html.

- Cordon Gavin and Gibson Matt. 2021. UK Will Not “Pitchfork Away” Investment from China, says Boris Johnson. Wales Online, October 19. https://www.walesonline.co.uk/news/uk-news/uk-not-pitchfork-away-investment-21898125.

- Crookes and Farnell. 2019. The UK’s Strategic Partnership with China beyond Brexit: Economic Opportunities Facing Political Constraints. Journal of current Chinese Affairs 48 (1).Google Scholar

- European Council on Foreign Relations. 2020. The Meaning of Systemic Rivalry: Europe and China Beyond the Pandemic. https://ecfr.eu/publication/the_meaning_of_systemic_rivalry_europe_and_china_beyond_the_pandemic/.

- Financial Times. 2020. China Envoy Warns of ‘Consequences’ if Britain Rejects Huawei. https://www.ft.com/content/3d67d1c1-98ff-439a-90a1-099c18621ee9.

- Foreign Affairs Committee. 2019. China and the Rules Based International System: Government Response the Committee’s 16th Report. https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmfaff/2362/236202.htm.

- Foreign and Commonwealth Office. 2019. E3 Joint Statement on the Situation in the South China Sea. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/e3-joint-statement-on-the-situation-in-the-south-china-sea.

- Foreign and Commonwealth Office. 2020a. UK Arms Embargo on Mainland China and Hong Kong. https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/uk-arms-embargo-on-mainland-china-and-hong-kong.

- Foreign and Commonwealth Office. 2020b. Hong Kong Joint Statement. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/joint-statement-on-hong-kong-november-2020b.

- Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office. 2021. UK Sanctions Perpetrators of Gross Human Rights Violations in Xinjiang, Alongside EU, Canada and US. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uk-sanctions-perpetrators-of-gross-human-rights-violations-in-xinjiang-alongside-eu-canada-and-us.

- Gaston Sophia and Rana Mitter. 2020. After the Golden Age, Resetting UK China Engagement. British Foreign Policy Group.Google Scholar

- Global Times. 2017. Time to lift EU’s Outdated Arms Embargo on China. https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1049431.shtml.

- Henderson Matthew. 2021. How the Chinese Communist Party ‘Positions’ the UK (Policy Paper N. SBIPP03). Council on Global Strategy. https://www.geostrategy.org.uk/app/uploads/2021/04/Policy-Paper-SBIPP03-22042021.pdf.

- HMSO. 2009. The UK and China: A Framework for Engagement. HMSO.Google Scholar

- House of Commons. 2019. China and the Rules Based International System. HC 612. https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmfaff/612/612.pdf.

- Huotari Mikko, Otero-Iglesias Miguel, Seaman John, and Ekman Alice. 2015. Mapping Europe China Relations: A Bottom Up Approach. Network on China. https://www.ifri.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/etnc_web_final_1-1.pdf.

- Jakes Lara, Crowley Michael, and Sanger David. 2020. Biden Chooses Antony Blinken, Defender of Global Alliances, as Secretary of State. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/22/us/politics/biden-antony-blinken-secretary-of-state.html.

- Kearsley Jonathan, and Bagshaw Eryk, 2020. ‘Not Here to be Bullied’: UK Weighs in on China Hitlist. https://www.smh.com.au/world/asia/not-here-to-be-bullied-uk-weighs-in-on-china-hitlist-20201126-p56i8y.html.

- Kearsley Jonathan, Bagshaw Eryk, and Galloway Anthony. 2020. If You Make China the Enemy, China Will be the Enemy: Beijing’s Fresh Threat to Australia. The Sidney Morning Herald. https://www.smh.com.au/world/asia/if-you-make-china-the-enemy-china-will-be-the-enemy-beijing-s-fresh-threat-to-australia-20201118-p56fqs.html.

- Kerry, Brown. 2019. The Future of UK China Relations. Newcastle: Agenda Publishing.Google Scholar

- McGleenon Brian. 2020. South China Sea: US Praises UK as Allies Prepare to Take Action Against Beijing. Daily Express. https://www.express.co.uk/news/world/1338733/south-china-sea-us-uk-royal-navy-hms-queen-elizabeth-world-war-3.

- Panda Ankit. 2020. Is the Time Right for Japan to Become Five Eyes’ ‘Sixth Eye’? The Diplomat. https://thediplomat.com/2020/08/is-the-time-right-for-japan-to-become-five-eyes-sixth-eye/.

- Parton Charles. 2019. China UK Relations: Where to Draw the Border Between Influence and Interference? (RUSI Occasional Paper) RUSI. https://www.rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/occasional-papers/china-uk-relations-where-draw-border-between-influence-and-interference.

- Parton Charles. 2020a. Towards a UK Strategy and Polices for Relations With China. The Policy Institute.Google Scholar

- Parton Charles. 2020b. UK Relations with China: Not Cold War, But A Values War; Not Decoupling, But Some Divergence. China Research Group. https://chinaresearchgroup.org/values-war#fn26.

- Parton Charles. 2021. Empty Threats? Policymaking Amidst Chinese Pressure. Council on Geostrategy. https://www.geostrategy.org.uk/research/empty-threats-policymaking-amidst-chinese-pressure/.

- Phillips Tom. 2015. Britain Has Made ‘Visionary Choice’ to Become China’s Best Friend. The Guardian, 18 October. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2015/oct/18/britian-has-made-visionary-choice-to-become-chinas-best-friend-says-xi.

- Philp, Catherine. 2020. Don’t Threaten Us, Warns China Envoy Liu Xiaoming. The Times, 18 July. https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/dont-threaten-us-warns-china-envoy-liu-xiaoming-622t9mbc6.

- Policy Exchange. 2020. A Very British Tilt. https://policyexchange.org.uk/publication/a-very-british-tilt/.

- Sevastopolou, Demetri, and Hille, Kathrin. 2022. US Holds High Level Talks With UK Over Threat to Taiwan. Financial Times, 2 May 2022. https://www.ft.com/content/b0991186-d511-54c-b5f0-9bd5b8ceee40.

- Six-Monthly Report on Hong Kong. 2015. July 2014–December 2014. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/415938/Hong_Kong_Six_Monthly_Report_July-Dec_2014.pdf.

- Six-Monthly Report on Hong Kong. 2021. July 2020–December 2020. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/992734/hong-kong-six-monthly-report-48-jul-dec-2020.pdf.

- Smith Julianne, Andrea Kendall-Taylor, Carisa Nietsche, and Ellison Laskowski. 2020. Charting a Transatlantic Course to Address China. https://www.cnas.org/publications/reports/charting-a-transatlantic-course-to-address-china.

- Summers Tim. 2015. UK-China Relations: Navigating a changing world. In Mapping Europe-China Relations: A Bottom-Up Approach. Report by the European Think Tank Network on China.Google Scholar

- The Diplomat. 2019. The Future of the Five Power Defense Arrangements. https://thediplomat.com/2019/11/the-future-of-the-five-power-defense-arrangements/.

- The Elements of the China Challengex. 2020. Policy Planning Staff. US Department of State.Google Scholar

- The Security and Defence Committee of the House of Lords. 2021. The UK and China’s Security and Trade Relationship: A Strategic Void.Google Scholar

- Truss, Liz. 2022. The Return of Geopolitics: Foreign Secretary’s Mansion House Speech at the Lord Mayor’s Easter Banquet. https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/foreign-secretarys-mansion-house-speech-at-the-lord-mayors-easter-banquet-the-return-of-geopolitics.

- UK Parliament. 2020. South China Sea: Freedom of Navigation (Vol. 679). https://hansard.parliament.uk/commons/2020-09-03/debates/99D50BD9-8C8A-4835-9C70-6E9A38585BC4/SouthChinaSeaFreedomOfNavigation.

- Wang, Yi. 2022. Press Conference. https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/eng/zxxx_662805/202203/t20220308_10649559.html.

- Watt Nicholas. 2013. David Cameron to Distance Britain from Dalai Lama During China Visit. The Guardian, November 30. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2013/nov/30/david-cameron-distance-britain-dalai-lama-china-visit.

- Watt Nicholas, Lewis Paul, and Branigan Tania. 2015. Us anger at Britain joining Chinese-led investment bank AIIB. The Guardian, March 13. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2015/mar/13/white-house-pointedly-asks-uk-to-use-its-voice-as-part-of-chinese-led-bank.

- Wintour Patrick. 2020. UK Should Tilt Foreign Policy to Indo-Pacific Region, Report Says. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2020/nov/22/uk-should-tilt-foreign-policy-to-indo-pacific-region-report-says.

Download references

Authors and Affiliations

- London, UKRoderic F. Wye

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Roderic F. Wye .

Editors and Affiliations

- Meilen, SwitzerlandSimona A. Grano

- Bern, Bern, SwitzerlandDavid Wei Feng Huang

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

As a medium-sized power, but one with particular global responsibilities and ambitions deriving from its position on the UN Security Council, the UK finds itself in a special situation in terms of a balancing to bandwagoning continuumFootnote1—in its response to China—in the light of the intense strategic competition between China and the US that has been emerging. The UK has until recently operated, as Australia, largely within the central hedging zone, seeking its own relationship with China, but remaining fundamentally committed to the alliance with the US. But that positioning underestimates the profound shifts that have taken place in Britain’s overall view and relationship with China. Less than a decade ago the UK was rejoicing in the so-called golden era of its bond with China, a description that seemed to be aligning the UK in some respects more closely with Chinese objectives (and certainly using Chinese-style language to describe the connection). The country is now considerably more China-sceptical.

This transition was initially gradual and marked by uncomfortable policy lurches, which appeared to derive from a lack of a clear and consistent strategic appreciation of the China challenge, and suggested a degree of incoherence in policymaking. Britain had been gradually becoming more vocal in its criticism of China and had been prepared to make political security gestures that were well understood to be irritating to China. But it remained keen to preserve and develop its economic relationship with China, though even that was increasingly a matter of contention at the political level. At the same time, the UK never wavered in taking the relationship with the US as the most fundamental and consistent element in its foreign and security policy. This did not mean blindly following every twist and turn of US policy towards China. The UK showed no interest in the confrontational trade policies introduced by President Trump and followed by his successor. Its view of the security challenge from China was of a somewhat different order from that of the US—goings on East Asia remained comparatively remote for the UK and other European governments.

Overall View of China

All of this has changed in the last couple of years. Firstly, the shock of COVID-19 and of China’s reaction to it has borne a significant impact on the global economy, trade and supply chains, which has reduced China’s attraction as a trading partner. Secondly, the Chinese crackdown in Hong Kong and Xinjiang led to a more critical view of China in most of the UK establishment. Even more fundamentally, the Russian invasion of Ukraine and ensuing reactions to it by the US, the EU and NATO (and of course the highly equivocal position taken by China) has tilted the UK decisively towards the “hard balancing” sector of the “Balancing Zone” (see Fig. 1.1 in Chapter 1 of this volume). This process has already been set in motion before the invasion—certainly in areas of technological and military security policy but less clearly in others. The announcement of the AUKUS partnership likewise represents a significant indication that the UK is moving in the direction of presenting a challenge to China’s increasing threat to East Asian security. It is worth noting that China was not directly named in the announcement of the new partnership, which was described as meant to protect the people and support a peaceful and rule-based international order, while bolstering the commitment to strengthen alliances with like-minded allies and deepen ties in the Indo-Pacific.Footnote2 The message, however, was very clear.

For many years, the UK had operated quite comfortably within the “soft balancing” subzone. “This geo-political change – the rise of China, the most important geo-political change in my children’s lifetime. It is the most important geo-political change in the 21st Century” (BBC Radio 4 2020). This thought, expressed here by the former UK Prime Minister Tony Blair, was commonplace in discussion of relations with China and underlined the on-going importance of properly and effectively managing relationships with China. The UK’s dealings with China are not simple nor straightforward. It is far more than a simple question of balancing the competing drives of commercial engagement while speaking up on human rights, as the relationship was frequently boiled down to, in public discourse. It is a wide-ranging relationship, covering many areas of activity. This obviously encompasses politics and economics, but also includes education, science and technology, culture and so on. Until recently, China did not figure high on the UK’s list of priorities, nor was the bilateral relationship between China and the UK given much academic or think tank consideration. This changed in recent years and there has been a string of well thought and persuasively argued considerations regarding the nature of the relationship and where it might be headed (Parton 2020a; Gaston and Mitter 2020; Kerry Brown 2019; Policy Exchange 2020). There are also a number of publications taking a closer look at the more interventionist policies pursued by the Chinese government and how these are beginning to impact on parts of UK society (Parton 2019; Hamilton and Ohlberg 2020; Henderson 2021).

As a case in point, the debate and public hesitancy over the decision as whether to allow Huawei to provide significant amounts of the future 5G network in the UK, followed by a similarly confused trail of decision-making, leading to the exclusion of Chinese firms from the project to build a nuclear reactor at Sizewell B, have served to underline the complexity and challenges of the relationship with China. The revelations of the establishment of a vast network of camps to control and subdue the Uighur population of Xinjiang, and the ruthless way in which China has imposed its will on Hong Kong, have highlighted the authoritarian nature of the Chinese government. The behaviour of the Chinese government and its role in the outbreak of and response to the COVID-19 pandemic has likewise deeply influenced public and official views of China and of how the UK should relate to it, prompting a profound re-evaluation, even before the decisive shift in UK policy, which seemed to follow Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The necessity for a re-evaluation—or reset in the words of Mitter and Gaston (2020)—of the relationship has come at a time of profound and rapid changes in the international and geo-political situation. A crucial structural factor arises out of the marked shift in comparative power between Britain and China, since China was able to overtake the UK in economic size almost 20 years ago; this, in turn, led to a situation which makes it easier for China to take the lead and the initiative in many areas (Summers 2015). The immediate effect of the invasion of Ukraine has been to shift UK policy decisively, at least in the security sphere, towards the “hard balancing” subzone, set in the “balancing zone” rather than in the “hedging zone”. How long this effect will continue and how much it will influence other aspects of the relationship is as yet unclear, but it is certain that a milestone has been passed.

Key Historical Features of the UK-China and UK–US Relationship

Among the middle-sized powers, the UK has a number of particular features which complicate the management of its relationships with both China and the US. These include: its historical bond with the US (the so-called special relationship); Britain’s decision to leave the European Union (Brexit); Britain’s own position as a middle power deriving from its historic legacy; and Britain’s historical relationship with China.

Britain has regularly played up its special relationship with the US—deriving ultimately from the Second World War and visions of the UK’s role, which are still deeply embedded in the UK’s political consciousness. But the relationship has historically tended to mean more to the UK than to the US, which sees the value and indeed the “distinctiveness” as much more limited. There have been periods when the UK liked to imagine itself as some sort of “bridge” both in the transatlantic relationship (particularly with the European Union), and sometimes in the relationship with China. In the latter case, UK policymakers have at times believed that they could nudge the US in a more sensible direction whenever the US seemed to have slipped off course. Brexit, however, has greatly reduced the UK’s foreign policy influence within Europe and the opportunities for the country to act as some form of transatlantic bridge.

The UK, however, has been very much ahead of other European countries in its provision of rhetorical and actual support to Ukraine since the invasion, perhaps reverting to its more traditional position as a faithful supporter of the US standpoint. How much this may influence the EU in its actions and posture towards the UK is still unclear but what is clear, is that the Ukraine crisis has caused a fundamental rethinking of Europe’s security architecture, which has a profound impact also on the UK-EU relationship.