A GATPM Report | London |

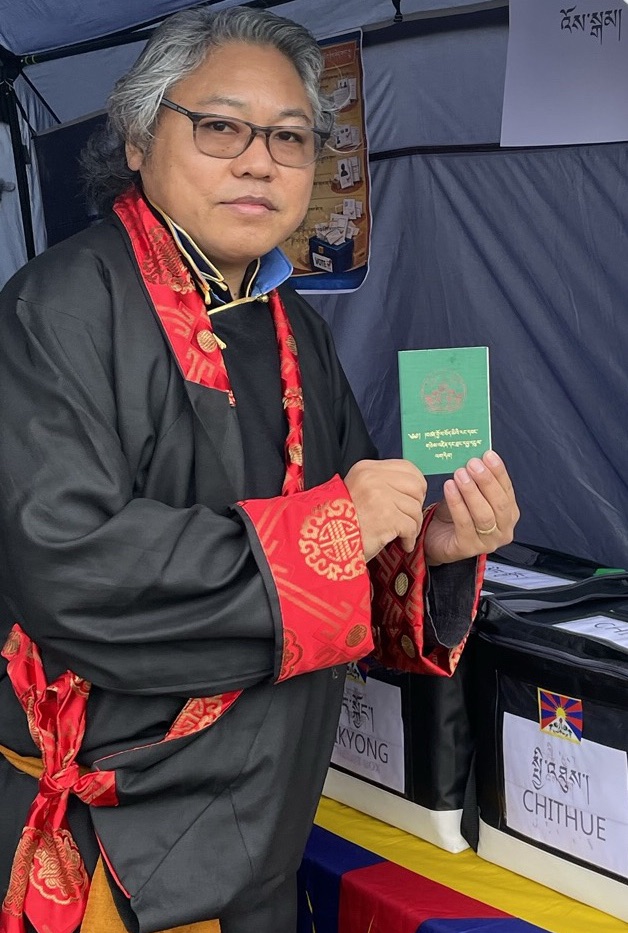

On Tuesday, 10 March 2026, Tibetans and supporters across London commemorated the 67th anniversary of the Tibetan National Uprising of 1959, renewing calls for freedom, justice, and human rights for the Tibetan people. The day brought together community members, parliamentarians, and human rights advocates through a series of events combining symbolic civic solidarity, peaceful demonstrations, and a public commemorative event.

Woolwich Town Hall – Civic Solidarity

The day began at Woolwich Town Hall, where the Tibetan national flag was displayed as a symbol of solidarity with the Tibetan people. The gathering was organised by the Greenwich Tibetan Association (GTA) in collaboration with the Royal Borough of Greenwich (RBG).

Although the formal flag-raising ceremony could not take place this year due to scaffolding and building repair works, the Mayor, Deputy Mayor, and Deputy Leader warmly welcomed members of the Tibetan community and local residents for a photo session with the Tibetan flag. The Mayor’s Office confirmed that the Tibet Flag hoisting ceremony will resume next year, reflecting the borough’s continued support for the Tibetan cause.

Whitehall Rally – Parliamentary Support

Participants then gathered at Whitehall, opposite Downing Street, at the heart of the United Kingdom’s political landscape, for a rally highlighting the ongoing human rights situation in Tibet.

Speakers included:

- Lord David Alton, Chair of the Joint Committee on Human Rights

- Alicia Kearns MP, Shadow Minister for Home Affairs and former Chair of the Foreign Affairs Select Committee

- Luke de Pulford, Co-founder and Executive Director of the Inter-Parliamentary Alliance on China (IPAC)

- Norman Baker, former UK Government Minister and a long-time Tibet supporter

- Phuntsok Norbu, Chairman of the Tibetan Community in Britain

Speakers emphasised the need for democratic governments to address ongoing human rights violations in Tibet and urged the Chinese government to respect the religious and cultural rights of the Tibetan people, including their right to determine their own spiritual leaders – particularly the recognition of the next Dalai Lama.

Following the rally, participants marched through central London in the annual Peace March, reaffirming the Tibetan people’s commitment to non-violence and peaceful advocacy.

Rally Outside the Chinese Embassy – Shared Struggles

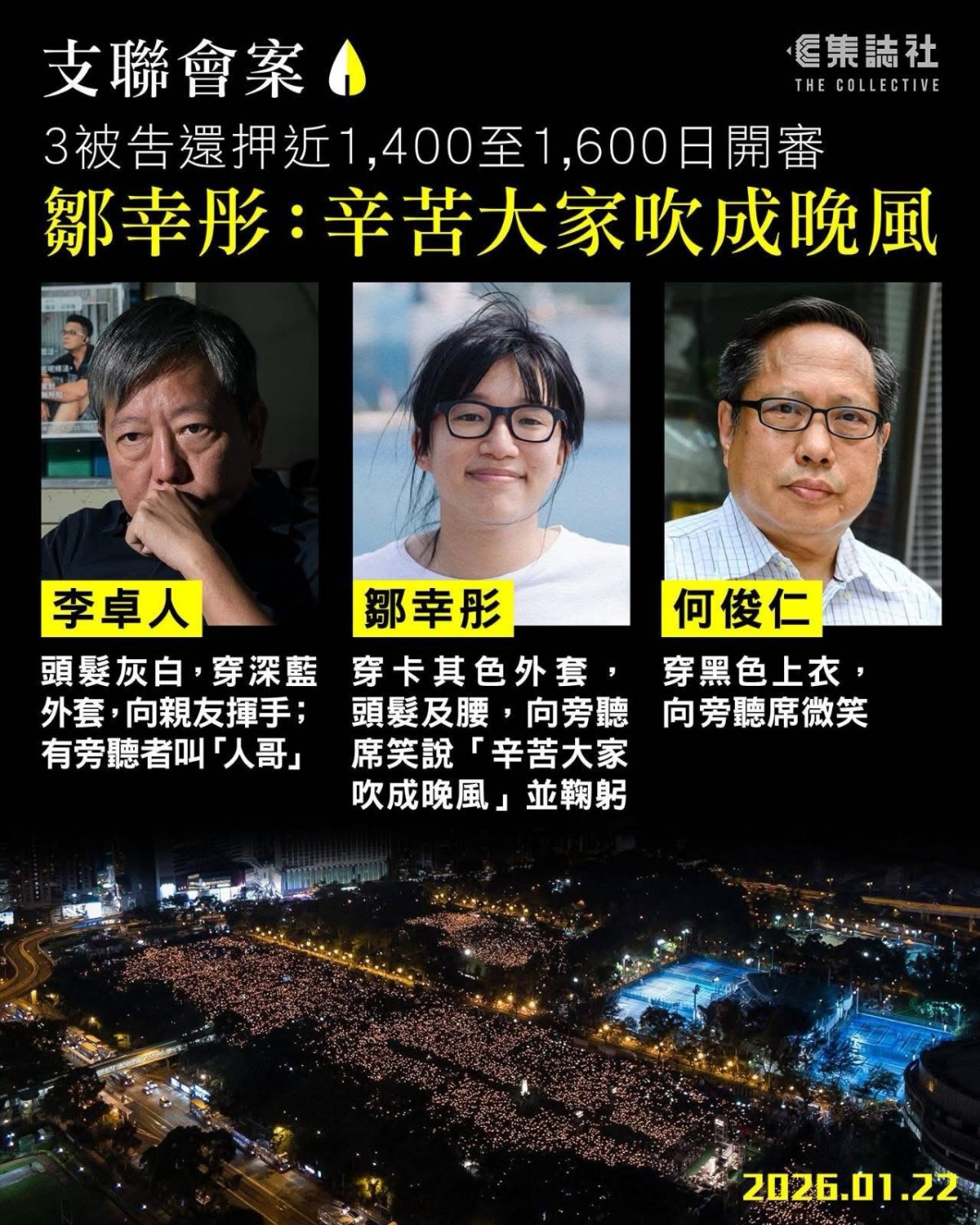

The march concluded outside the Chinese Embassy, where activists from multiple communities expressed solidarity with Tibet and other persecuted peoples.

Speakers included:

- Tenzin Sangmo, Regional Coordinator of the Tibetan Community in Britain

- Clara Cheung, Hong Kong democracy activist and former District Councillor

- Rahima Mahmut, Executive Director of Stop Uyghur Genocide

- Khando Norbu, Director of Students for a Free Tibet

They highlighted the shared challenges faced by Tibetans, Uyghurs, and Hong Kongers, stressing the importance of international solidarity in defending human rights and freedom. Chants of “Free Tibet,” “China Out of Tibet,” “Human Rights in Tibet,” “Stop the Killing in Tibet,” and “Long Live the Dalai Lama” rang out, echoing across the Chinese Embassy compound where officials were at work.

Tibetan Commemorative Event – Indian YMCA

The day-long programme, organised by the Tibetan Community in Britain in association with the Global Alliance for Tibet & Persecuted Minorities, Free Tibet, Students for a Free Tibet, and the Voluntary Tibet Advocacy Group, concluded with a commemorative function at the Indian YMCA.

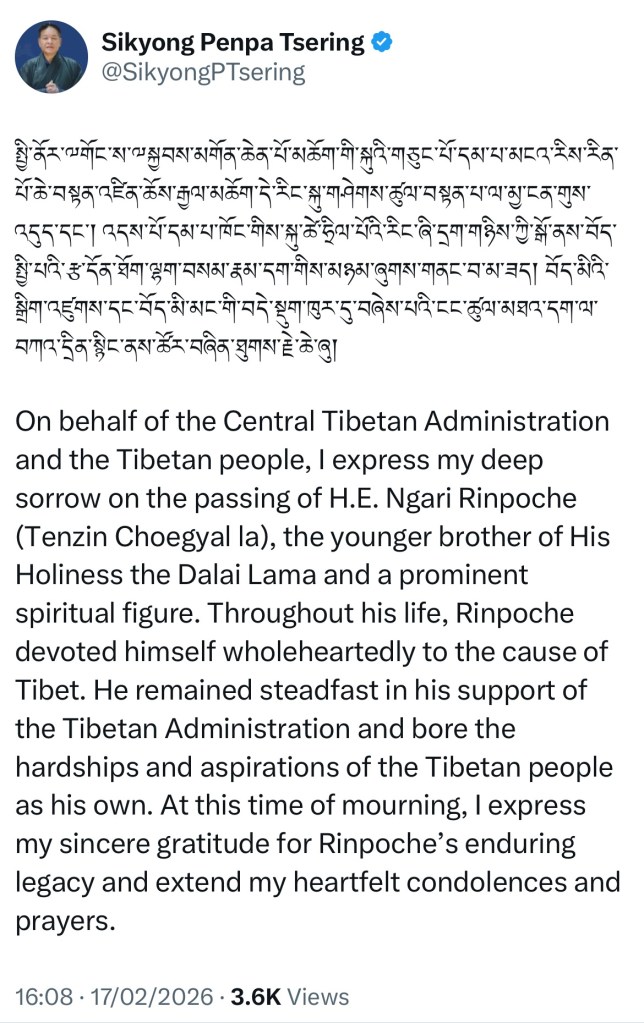

Held under the theme “Year of Compassion: Calling for Freedom and Justice in Tibet,” the function opened with the Tibetan national anthem, followed by a one-minute silence, a Buddhist prayer for world peace, and commemorative songs honouring those who sacrificed their lives during the 1959 uprising.

Her Excellency Madam Tsering Yangkey, Representative of His Holiness the Dalai Lama in the United Kingdom, read the official Kashag statement and spoke about the importance of international solidarity. In an emotional address in Tibetan, she emphasised the urgent need to safeguard the Tibetan language, culture, and identity.

Phuntsok Norbu, Chairman of the Tibetan Community in Britain, highlighted the unity and resilience of the Tibetan diaspora and encouraged continued advocacy to ensure Tibet’s voice remains strong in the United Kingdom.

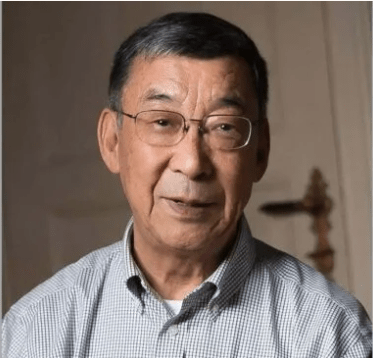

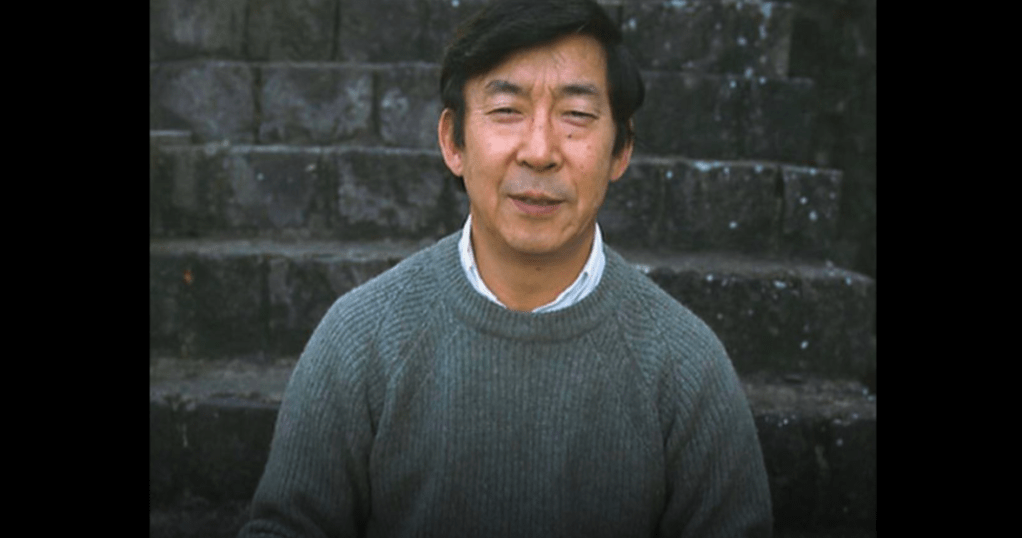

A deeply thoughtful address was delivered by Dr. Shao Jiang, a Chinese dissident, scholar-activist, and former student leader during the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests, who was imprisoned as a political prisoner of conscience for his activism.

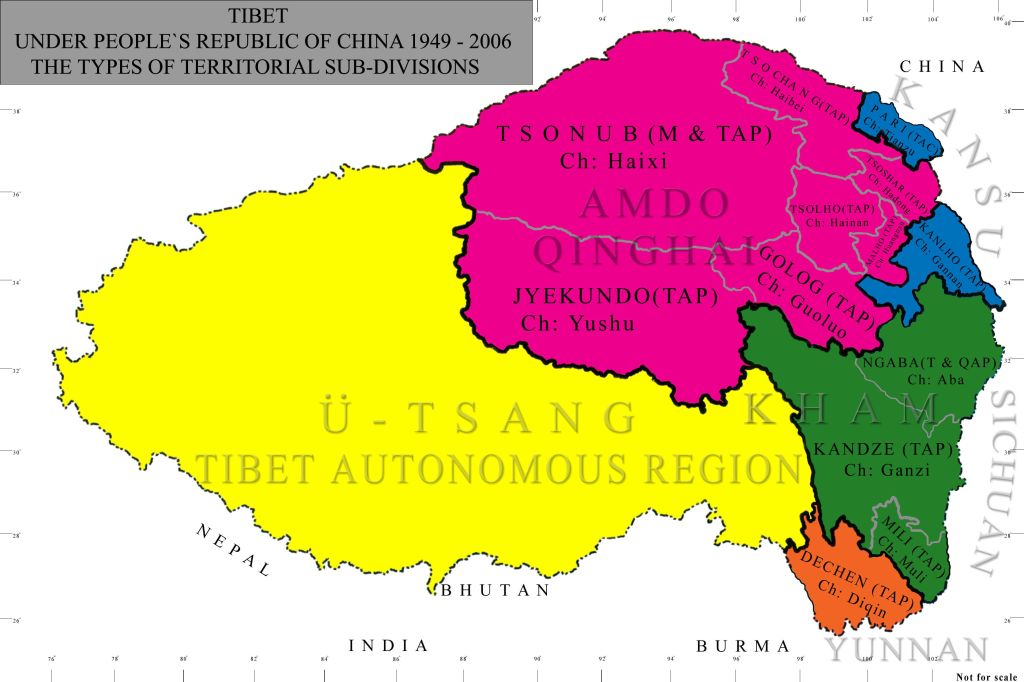

Reflecting on decades of Chinese rule in Tibet, Dr. Jiang argued that official narratives may have changed, but the underlying system of control has remained constant:

“For decades, the Chinese Communist Party has enforced its illegal occupation of Tibet under shifting slogans… The slogans change. The structure does not. Tibet has been ruled without Tibetan consent.”

He outlined four interconnected areas shaping Tibetan life today – land and livelihood, environment, language and culture, and religion – describing them as part of a broader structure of political domination.

“Land enclosure, resource extraction, linguistic marginalisation, and religious control form one integrated system.”

Dr. Jiang described the displacement of Tibetan communities, ecological exploitation of the Tibetan plateau, suppression of Tibetan language in education, and restrictions on Tibetan Buddhism.

Despite these challenges, he highlighted the resilience of Tibetans in exile, pointing to their democratic institutions and cultural initiatives as evidence of their capacity to shape their own future.

He concluded with a message of determination:

“Power cannot erase history. It cannot extinguish a people’s identity. We remain committed to self-determination, to basic freedoms, and to democratic participation… Tibet will be free.”

Advocacy and Youth Leadership

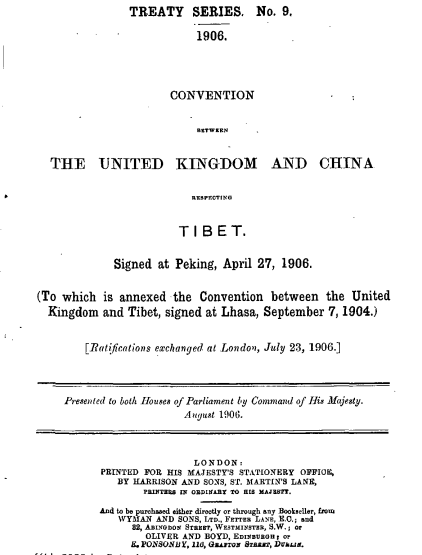

Benedict Rogers, Senior Director at Fortify Rights and co-founder of Hong Kong Watch, reaffirmed his solidarity with Tibet. He recalled meeting the Dalai Lama in Dharamsala three years ago and noted that ahead of Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer’s visit to China in January 2026, 19 human rights organisations had urged the UK Government to raise concerns about Tibet.

Youth speakers Tenzin Rabga of Free Tibet and Kunsel Dorjee of Students for a Free Tibet spoke about the importance of sustaining the Tibetan freedom movement through youth activism and global grassroots engagement.

The programme concluded with a vote of thanks by Drukthar Gyal, General Secretary of the Tibetan Community in Britain.

Tsering Passang, Founder-Chair of the Global Alliance for Tibet & Persecuted Minorities, who served as host of the afternoon event, reflected on the significance of the day:

“We honour the courage of the Tibetan people who rose up in Lhasa on 10 March 1959, and we reaffirm our commitment to freedom, justice, human rights, and the preservation of Tibet’s unique cultural and spiritual heritage.

“Sixty-seven years ago, tens of thousands of Tibetans rose peacefully to defend their freedom, dignity, identity, and their spiritual leader, His Holiness the Dalai Lama. Their courage and sacrifice continue to inspire Tibetans and supporters across the world. As we commemorate this day in London, we gather in remembrance, solidarity, and hope – renewing our shared commitment to freedom, justice, and human dignity for the Tibetan people.”

Continuing the Call for Justice

The events held across Woolwich Town Hall, Whitehall, the Chinese Embassy, and the Indian YMCA demonstrated the strength of international solidarity with Tibet.

Speakers from Tibetan, Uyghur, and Hong Kong communities emphasised the interconnected nature of struggles for freedom and human dignity.

Sixty-seven years after the uprising in Lhasa, the message resonating across London was clear:

The Tibetan struggle for freedom, dignity, and cultural survival continues – sustained by resilience, global solidarity, and an enduring hope for justice.

Today, more than 1,500 Tibetans remain imprisoned for exercising their fundamental rights, while restrictions on language, religion, and cultural expression persist inside Tibet. Commemorations such as these ensure that the voices of Tibetans – both inside Tibet and in exile – continue to be heard around the world.

Photos: Drukthar Gyal | 10 March 2026

![[A GATPM Statement] Global Alliance for Tibet & Persecuted Minorities Voices Serious Concern Following UK Government Approval of China’s Controversial Mega-Embassy at Royal Mint Court](https://tsamtruk.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/image-2.png?w=641)

You must be logged in to post a comment.