Tsering Passang | 26 December 2025

In this article, Tsering Passang critically examines how historically inaccurate public statements by an elected Tibetan leader risk weakening the credibility, coherence, and moral authority of the Tibetan cause, underscoring the responsibility of leadership to uphold historical accuracy.

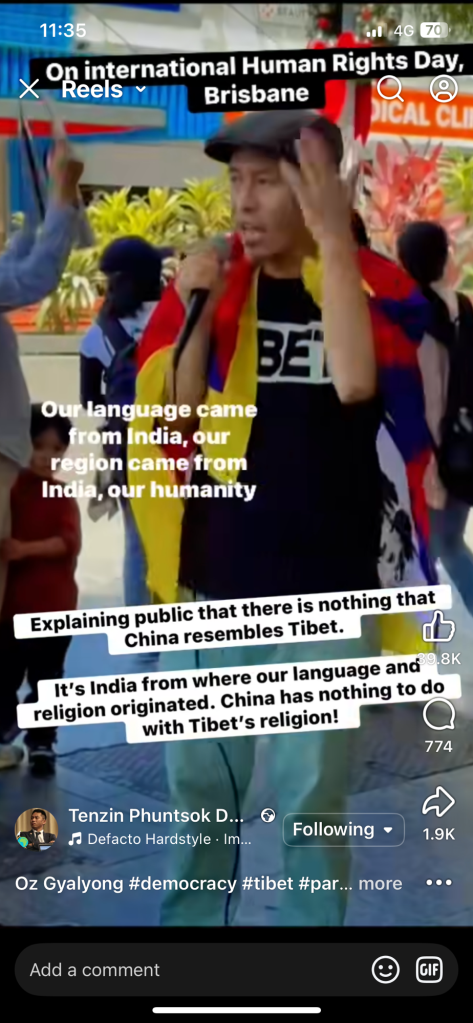

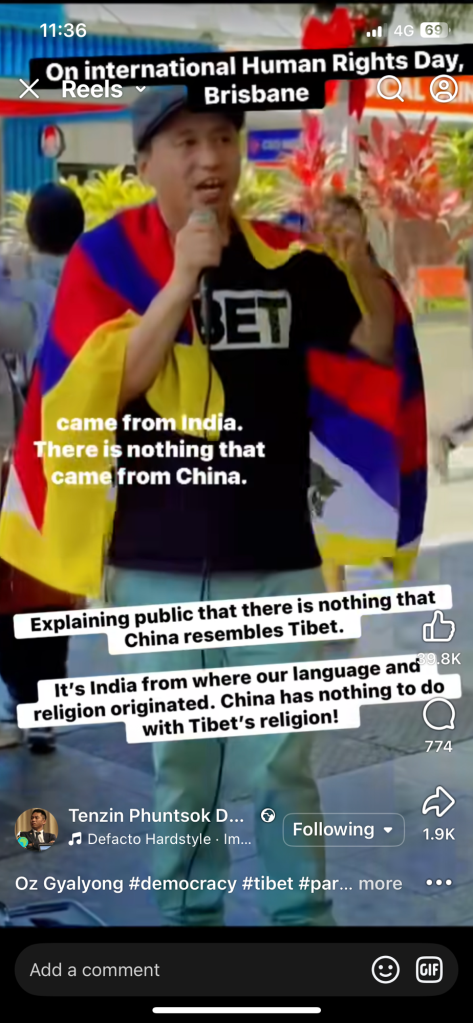

Tenzin Phuntsok Doring’s recent viral video — reportedly viewed by over one million people — has attracted significant attention across Tibetan and international communities. As a serving Tibetan Member of Parliament speaking during a public protest outside a Chinese Consulate in Australia, his words carry influence far beyond the immediate context of protest. Precisely because of this responsibility, the factual inaccuracies and sweeping historical claims made in the clip demand careful, principled, and constructive scrutiny.

In the video, Mr. Doring asserts that the Tibetan language came from India, Tibetan religion came from India, and Tibetan humanity came from India, further stating that nothing came from China. He also states that Tibet was never part of China and never wanted to be part of China, while strongly implying that Tibet’s ancient Bon religion originated in India.

While such statements may have been intended to galvanise emotional solidarity and political resolve, they significantly oversimplify — and in several instances misrepresent — Tibetan history. When such narratives are amplified by an elected representative, they risk undermining intellectual credibility, political coherence, and ultimately the moral authority of the Tibetan struggle itself.

Language, Culture, and Historical Complexity

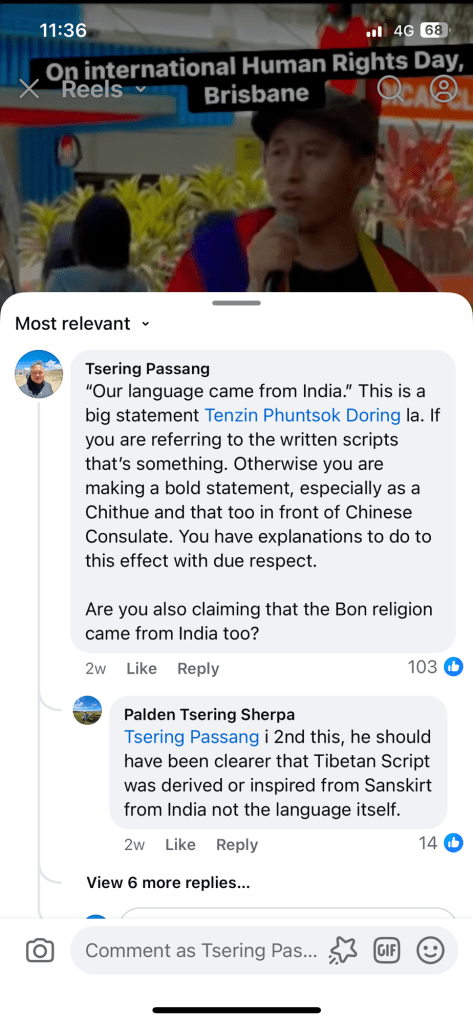

It is historically inaccurate to claim that the Tibetan language “came from India.” While the Tibetan script was developed in the 7th century with inspiration from Indian writing systems — particularly during the reign of King Songtsen Gampo — this does not mean the Tibetan language itself originated in India. Tibetan is a Tibeto-Burman language with deep indigenous roots on the Tibetan Plateau. Scriptural or orthographic influence is not synonymous with linguistic origin, and conflating the two weakens an otherwise rich and well-documented historical narrative.

Similarly, Tibetan Buddhism undeniably absorbed profound philosophical, textual, and institutional influences from India’s Nalanda Buddhist tradition with the profound help of great Indian Buddhist scholars. This is a source of historical pride and spiritual connection, not contention. However, to claim that Tibetan religion as a whole came from India effectively erases the indigenous religious and cultural traditions that existed long before Buddhism’s arrival.

Most concerning is the implication that Bon originated in India. This claim is factually unsound. Bon is widely recognised by scholars as an indigenous Tibetan tradition, even though it later incorporated Buddhist elements and engaged in sustained dialogue with the Indian religious thought. Portraying Bon as Indian in origin distorts history and marginalises a foundational pillar of Tibetan civilisation and identity.

Political Messaging and Historical Responsibility

The assertion that “there is nothing that came from China” is another absolutist statement that does not withstand historical scrutiny. Tibet’s historical relationship with successive Chinese dynasties, Mongol polities, and neighbouring regions was complex, evolving, and often contested. Serious Tibetan scholarship has long acknowledged this complexity rather than denying interaction altogether.

At the same time, it is equally important to state accurately that Tibet was regarded by Tibetans as an independent nation for much of its history, including periods when Tibetan emperors exercised influence or invaded parts of mainland China, until Communist China invaded Tibet in 1950. Historical interactions — such as King Songtsen Gampo’s marriage to the Chinese Princess Wencheng and the arrival of the Jowo statue — cannot simply be erased or selectively ignored. A mature and credible historical narrative acknowledges interaction without surrendering self-determination, identity, or political claims.

More critically, such rhetoric sits uneasily with the Middle-Way Approach, the official policy adopted by the Tibetan Parliament-in-Exile and consistently championed by His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama. The Middle-Way policy explicitly seeks genuine autonomy within the framework of the Constitution of the People’s Republic of China, not outright independence. Public messaging that categorically rejects any association with China risks contradicting this long-standing policy and creating confusion among Tibetans, supporters, and international stakeholders alike.

The Stakes of Public Inaccuracy

Mr. Tenzin Phuntsok Doring is not a casual social media commentator. Born in Tibet, educated in India to the MPhil level, and entrusted as an elected lawmaker, he bears responsibility for shaping Tibetan political discourse and legislative direction. When a sitting parliamentarian disseminates historically inaccurate narratives to a global audience, it raises serious concerns about the boundary between principled advocacy and disinformation.

Notably, I personally sought to encourage Mr. Doring to reflect on these inaccuracies and take corrective action after the video began circulating widely. Unfortunately, no such correction has been made. Instead, earlier today, he further shared the same viral clip on his social media platform amid the ongoing Tibetan parliamentary election campaign, prominently displaying the Tibetan national flag. This action deepens concern, as it risks politicising historical inaccuracies for electoral visibility rather than addressing them responsibly.

At a time when Tibetans are striving for international credibility, moral authority, and a principled commitment to nonviolence, accuracy is not optional — it is essential. Emotional mobilisation built on weak or inaccurate historical claims can be easily dismantled by critics and exploited by adversaries, ultimately harming the very cause it seeks to advance.

A Call for Reflection and Correction

This moment should not be approached defensively, but embraced as an opportunity for reflection, learning, and accountability. A public clarification or correction would demonstrate intellectual integrity, leadership maturity, and genuine respect for the Tibetan people’s history.

If Tibetan leaders wish to challenge Chinese state narratives effectively, they must do so with rigour, nuance, and factual confidence. Acknowledging historical complexity does not weaken the Tibetan cause — it strengthens it.

The Tibetan people deserve representation that honours both their past and their future truthfully, responsibly, and wisely.