By Tsering Passang, London (UK)

Recent developments in European museums, specifically the Musée du quai Branly and the Musée Guimet in Paris, have sparked controversy over their presentation of Tibet as “Xizang.” This renaming aligns with Beijing’s political narrative, raising concerns about how Western cultural institutions are increasingly vulnerable to external political pressures. The use of “Xizang” is emblematic of China’s international campaign to shape global discourse on Tibet, a campaign driven by the establishment of the Xizang International Communication Centre.

The Historical Context of Tibet and “Xizang”

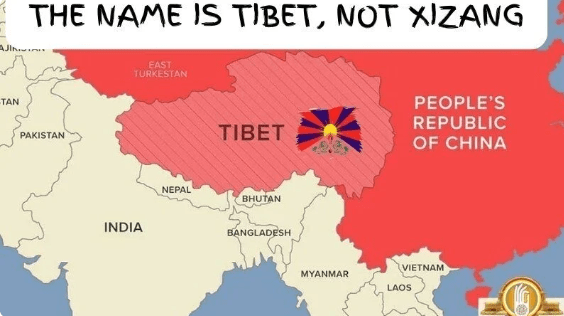

The term “Xizang,” which translates to “Western Treasure House,” is the official Chinese designation for Tibet and is heavily promoted by Beijing to reinforce its sovereignty claims. For years, China has sought international adoption of the term, as part of a broader strategy to control the narrative surrounding Tibet’s history, culture, and political status.

China’s Renewed Global Communication Strategy

Tibet, a landlocked Buddhist region with a rich cultural and religious heritage, has long been at the centre of conflict with the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Tibetans view their language, religion, and identity as distinct, while China claims Tibet as an inseparable part of its territory. This narrative became official after China’s 1950 military invasion, which culminated in the full annexation of Tibet following the Dalai Lama’s exile to India in March 1959. In response to China’s aggression, Tibetans resisted, first with poorly-equipped weapons in the 1950s, and later through guerrilla warfare by voluntary fighters operating from Mustang, Nepal from 1960 until 1974. The Central Tibetan Administration, also known as the Tibetan government-in-exile, has called for genuine autonomy for decades, though Beijing has consistently rejected these appeals.

Recently, China launched the Xizang International Communication Centre, a key initiative in its ongoing effort to reshape global perceptions of Tibet. Operating under the Chinese government’s Tibet propaganda apparatus, the centre’s primary goal is to promote Beijing’s preferred version of Tibet’s history and its integration into China. This effort extends beyond domestic propaganda, aiming to influence international media, academia, and cultural institutions by disseminating a narrative aligned with China’s political stance on Tibet.

This communication centre is part of China’s broader strategy to expand its “soft power” and shape global opinions. Through institutions like these, China seeks to redefine international understanding of Tibet, often downplaying Tibetans’ calls for greater autonomy and historical claims to independence. The international adoption of “Xizang” is viewed as a key victory in this campaign.

Musée du quai Branly and Musée Guimet: A Case of Influence

Against this backdrop, two respected Parisian institutions – Musée du quai Branly and Musée Guimet, both renowned for their focus on world cultures – have come under scrutiny for using the term “Xizang” and “Himalayan World” respectively in their exhibits on Tibet. While both museums are respected for their dedication to cultural preservation and education, critics argue that their decision to use “Xizang” reflects undue influence from Beijing, potentially compromising the historical integrity of their displays.

Adopting this terminology is seen by many as an implicit endorsement of China’s political agenda. It risks erasing the distinct cultural and historical identity that Tibetans and their supporters have fought to preserve. By using “Xizang” in place of “Tibet,” these institutions appear to align themselves with China’s narrative, raising concerns about the role of Western museums in maintaining objective representations of global histories.

The Role of Cultural Institutions in Historical Representation

Museums are powerful custodians of culture, history, and knowledge, playing a crucial role in shaping public understanding. They are often viewed as impartial entities that educate the public on complex historical narratives. However, the cases of Musée du quai Branly and Musée Guimet demonstrate that even cultural institutions are not immune to political influence.

Pressure to align with international diplomatic or economic relationships can lead to decisions that prioritise geopolitical considerations over historical accuracy. The decision to refer to Tibet as “Xizang” may be perceived as a concession to China’s growing global influence, potentially at the expense of Tibet’s distinct identity and history.

This shift is part of a broader trend of Beijing’s expanding political reach into cultural and educational spaces around the world. The controversial Confucius Institutes in various Western countries provide another example of China’s soft power tactics. By influencing how Tibet is represented in prestigious Western institutions, China is gaining ground in its effort to control the international narrative about the region.

The Implications of Political Influence on Cultural Narratives

The consequences of this political influence are significant. For Tibetans and advocates of self-determination, the use of “Xizang” represents more than a simple linguistic change; it symbolises the erasure of their cultural and historical identity. Tibet has a long history of resistance and calls for independence, and the adoption of China’s terminology risks diminishing the visibility of this struggle on the global stage.

Furthermore, the willingness of Western institutions to adopt Beijing’s terminology raises questions about how far cultural organisations are willing to compromise their integrity under external pressure. Museums, which should offer unbiased presentations of history, now risk becoming conduits for state-sponsored narratives.

Conclusion

The decision by Musée du quai Branly and Musée Guimet to use “Xizang” in reference to Tibet underscores the growing political influence that Beijing exerts on global cultural institutions. This shift is occurring against the backdrop of China’s broader efforts, exemplified by the Xizang International Communication Centre, to reshape global discourse surrounding Tibet. As China expands its reach, cultural institutions worldwide face a crucial choice: whether to uphold their commitment to historical accuracy and independence or yield to political influence. This decision will not only impact the representation of Tibet but could also set a precedent for how global narratives are shaped in the future.

*Tsering Passang, London (UK) is the founder and chair of the Global Alliance for Tibet & Persecuted Minorities.

USEFUL LINKS

One thought on “The Influence of Beijing on Western Cultural Institutions: The Case of Tibet’s Renaming and Communist China’s Global Narrative Push”